|

Separation of Church and State?

Imprimis

www.hillsdale.edu

Origins and Dangers of the ‘Wall of Separation’ Between Church

and State

October 2006

Daniel

L. Dreisbach

Professor of Justice, Law and Society, American University

Professor of Justice, Law and Society is a professor in the School of Public Affairs at American University

in Washington, D.C., as well as

the William E. Simon Fellow in Religion and Public Life in the James Madison Program at Princeton University. He received his D.Phil. from Oxford University and his J.D. from the University of Virginia. He is author or editor of numerous books, including Thomas Jefferson

and the Wall of Separation Between Church and State; The Founders on God and Government; Religion and Political Culture in

Jefferson’s Virginia; and Real Threat and Mere Shadow: Religious Liberty and the First Amendment.

The

following is adapted from a lecture delivered at Hillsdale College on September 12, 2006, during a Center for Constructive

Alternatives seminar on the topic, "Church and State: History and Theory."

No metaphor in American letters has had a greater influence on law and policy than Thomas Jefferson’s

"wall of separation between church and state." For many Americans, this metaphor has supplanted the actual text of the First

Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and it has become the locus classicus of the notion that the First Amendment separated

religion and the civil state, thereby mandating a strictly secular polity.

More important, the judiciary has embraced this figurative language as a virtual rule of constitutional law

and as the organizing theme of church-state jurisprudence. Writing for the U.S. Supreme Court in 1948, Justice Hugo L. Black

asserted that the justices had "agreed that the First Amendment’s language, properly interpreted, had erected a wall

of separation between Church and State." The continuing influence of this wall is evident in the Court’s most recent

church-state pronouncements.

The rhetoric of church-state separation has been a part of western political discourse for many centuries, but

it has only lately come to a place of prominence in American constitutional law and discourse. What is the source of the "wall

of separation" metaphor so frequently referenced today? How has this symbol of strict separation between religion and public

life become so influential in American legal and political thought? Most important, what are the policy and legal consequences

of the ascendancy of separationist rhetoric and of the transformation of "separation of church and state" from a much-debated

political idea to a doctrine of constitutional law embraced by the nation’s highest court?

The Wall that Jefferson Built

On New Year’s Day, 1802, President Jefferson penned a missive to the Baptist Association of Danbury,

Connecticut. The Baptists had written the new president a "fan" letter in October 1801, congratulating him on his election

to the "chief Magistracy in the United States."

They celebrated his zealous advocacy for religious liberty and chastised those who had criticized him "as an enemy of religion[,]

Law & good order because he will not, dares not assume the prerogative of Jehovah and make Laws to govern the Kingdom of Christ." At the time, the Congregationalist Church was still legally established in Connecticut and the Federalist party controlled New England

politics. Thus the Danbury Baptists were outsiders'a beleaguered religious and political minority in a state where a Congregationalist-Federalist

party establishment dominated public life. They were drawn to Jefferson’s political

cause because of his celebrated advocacy for religious liberty.

In a carefully crafted reply, the president allied himself with the New England Baptists in their struggle to

enjoy the right of conscience as an inalienable right-not merely as a favor granted, and subject to withdrawal, by the civil

state:

Believing with you that religion is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account

to none other for his faith or his worship, that the legitimate powers of government reach actions only, & not opinions,

I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature

should "make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof," thus building a wall

of separation between Church & State.

This missive was written in the wake of the bitter presidential contest of 1800. Candidate Jefferson’s religion, or the alleged lack thereof, was a critical issue in the campaign. His Federalist foes

vilified him as an "infidel" and "atheist." The campaign rhetoric was so vitriolic that, when news of Jefferson’s election swept across the country, housewives in New England

were seen burying family Bibles in their gardens or hiding them in wells because they expected the Holy Scriptures to be confiscated

and burned by the new administration in Washington. (These fears

resonated with Americans who had received alarming reports of the French Revolution, which Jefferson

was said to support, and the widespread desecration of religious sanctuaries and symbols in France.) Jefferson wrote to these pious Baptists to reassure them of his continuing

commitment to their right of conscience and to strike back at the Federalist-Congregationalist establishment in Connecticut for shamelessly vilifying him in the recent campaign.

Several features of Jefferson’s letter challenge conventional, strictly secular constructions

of his famous metaphor. First, the metaphor rests on a cluster of explicitly religious propositions (i.e., "that religion

is a matter which lies solely between Man & his God, that he owes account to none other for his faith or his worship").

Second, Jefferson’s wall was constructed in the service of the free exercise

of religion. Use of the metaphor to restrict religious exercise (e.g., to disallow a citizen’s religious expression

in the public square) conflicts with the very principle Jefferson hoped his metaphor

would advance. Third, Jefferson concluded his presidential missive with a prayer, reciprocating his

Baptist correspondents’ "kind prayers for the protection & blessing of the common father and creator of man." Ironically,

some strict separationists today contend that such solemn words in a presidential address violate a constitutional "wall of

separation."

The conventional wisdom is that Jefferson’s wall represents

a universal principle concerning the prudential and constitutional relationship between religion and the civil state. In fact,

this wall had less to do with the separation between religion and all civil government than with the separation between

the national and state governments on matters pertaining to religion (such as official proclamations of days of prayer, fasting,

and thanksgiving). The "wall of separation" was a metaphoric construction of the First Amendment, which Jefferson time and again said imposed its restrictions on the national government only (see, e.g., Jefferson’s 1798 draft of the Kentucky Resolutions).

In other words, Jefferson’s wall separated the national government on one side from state

governments and religious authorities on the other. This construction is consistent with a virtually unchallenged assumption

of the early constitutional era: the First Amendment in particular and the Bill of Rights in general affirmed the fundamental

constitutional principle of federalism. The First Amendment, as originally understood, had little substantive content apart

from its affirmation that the national government was denied all power over religious matters. Jurisdiction in such concerns

was reserved to individual citizens, religious societies, and state governments. (Of course, this original understanding of

the First Amendment was turned on its head by the modern U.S. Supreme Court’s "incorporation" of the First Amendment

into the Fourteenth Amendment.)

The Metaphor Enters Public Discourse

By late January 1802, printed copies of Jefferson’s reply to the

Danbury Baptists began appearing in New England newspapers. The letter, however, was not accessible to a wide audience

until it was reprinted in the first major collection of Jefferson’s papers, published

in the mid-19th century.

The phrase "wall of separation" entered the lexicon of American law in the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1878

ruling in Reynolds v. United States, although most scholars agree that the wall metaphor played no role in the Court’s

reasoning. Chief Justice Morrison R. Waite, who authored the opinion, was drawn to another clause in Jefferson’s text. The Reynolds Court, in short, was drawn to the passage, not to advance a strict separation

between church and state, but to support the proposition that the legitimate powers of civil government could reach men’s

actions only and not their opinions.

Nearly seven decades later, in the landmark case of Everson v. Board of Education (1947), the Supreme

Court "rediscovered" the metaphor and elevated it to constitutional doctrine. Citing no source or authority other than Reynolds,

Justice Hugo L. Black, writing for the majority, invoked the Danbury letter’s

"wall of separation" passage in support of his strict separationist interpretation of the First Amendment prohibition on laws

"respecting an establishment of religion." "In the words of Jefferson," he famously declared,

the First Amendment has erected "‘a wall of separation between church and State’. . . . That wall must be kept

high and impregnable. We could not approve the slightest breach." In even more sweeping terms, Justice Wiley B. Rutledge asserted

in a separate opinion that the First Amendment’s purpose was "to uproot" all religious establishments and "to create

a complete and permanent separation of the spheres of religious activity and civil authority by comprehensively forbidding

every form of public aid or support for religion." This rhetoric, more than any other, set the terms and the tone for a strict

separationist jurisprudence that reached ascendancy on the Court in the second half of the 20th century.

Like Reynolds, the Everson ruling was replete with references to history, especially the

roles played by Jefferson and Madison in the Virginia disestablishment

struggles in the tumultuous decade following independence from Great Britain. Jefferson was depicted as a leading architect of the First Amendment despite

the fact that he was in France when the measure was drafted by the First Federal Congress in 1789.

Black and his judicial brethren also encountered the metaphor in briefs filed in Everson. In a lengthy

discussion of history supporting the proposition that "separation of church and state is a fundamental American principle,"

an amicus brief filed by the American Civil Liberties Union quoted the clause from the Danbury letter containing the "wall of separation" image. The ACLU ominously concluded that the challenged state statute,

which provided state reimbursements for the transportation of students to and from parochial schools, "constitutes a definite

crack in the wall of separation between church and state. Such cracks have a tendency to widen beyond repair unless promptly

sealed up."

Shortly after the Everson ruling was handed down, the metaphor began to proliferate in books and articles.

In a 1949 best-selling anti-Catholic polemic, American Freedom and Catholic Power, Paul Blanshard advocated an uncompromising

political and legal platform favoring "a wall of separation between church and state." Protestants and Other Americans United

for the Separation of Church and State (an organization today known by the more politically correct appellation of Americans

United for Separation of Church and State), a leading strict-separationist advocacy organization, wrote the phrase into its

1948 founding manifesto. Among the "immediate objectives" of this new organization was "[t]o resist every attempt by law or

the administration of law further to widen the breach in the wall of separation of church and state."

The

Supreme Court frequently and favorably referenced the "wall of separation" in the cases that followed. In McCollum v. Board

of Education (1948), the Court essentially constitutionalized Jefferson’s phrase,

subtly and blithely substituting his figurative language for the literal text of the First Amendment. In the last half of

the 20th century, the metaphor emerged as the defining motif for church-state jurisprudence, thereby elevating a strict separationist

construction of the First Amendment to accepted dogma among jurists and commentators.

The Trouble with Metaphors in the Law

Metaphors are a valuable literary device. They enrich language by making it dramatic and colorful, rendering

abstract concepts concrete, condensing complex concepts into a few words, and unleashing creative and analogical insights.

But their uncritical use can lead to confusion and distortion. At its heart, metaphor compares two or more things that are

not, in fact, identical. A metaphor’s literal meaning is used non-literally in a comparison with its subject. While

the comparison may yield useful insights, the dissimilarities between the metaphor and its subject, if not acknowledged, can

distort or pollute one’s understanding of the subject. If attributes of the metaphor are erroneously or misleadingly

assigned to the subject and the distortion goes unchallenged, then the metaphor may alter the understanding of the underlying

subject. The more appealing and powerful a metaphor, the more it tends to supplant or overshadow the original subject, and

the more one is unable to contemplate the subject apart from its metaphoric formulation. Thus, distortions perpetuated by

the metaphor are sustained and even magnified. This is the lesson of the "wall of separation" metaphor.

The judiciary’s reliance on an extra-constitutional metaphor as a substitute for the text of the First

Amendment almost inevitably distorts constitutional principles governing church-state relationships. Although the "wall of

separation" may felicitously express some aspects of First Amendment law, it seriously misrepresents or obscures others, and

has become a source of much mischief in modern church-state jurisprudence. It has reconceptualized-indeed, misconceptualized-First

Amendment principles in at least two important ways.

First, Jefferson’s trope emphasizes separation between church and state?unlike

the First Amendment, which speaks in terms of the non-establishment and free exercise of religion. (Although these terms are

often conflated today, in the lexicon of 1802, the expansive concept of "separation" was distinct from the narrow institutional

concept of "non-establishment.") Jefferson’s Baptist correspondents, who agitated for disestablishment

but not for separation, were apparently discomfited by the figurative phrase and, perhaps, even sought to suppress the president’s

letter. They, like many Americans, feared that the erection of such a wall would separate religious influences from public

life and policy. Few evangelical dissenters (including the Baptists) challenged the widespread assumption of the age that

republican government and civic virtue were dependent on a moral people and that religion supported and nurtured morality.

Second,

a wall is a bilateral barrier that inhibits the activities of both the civil government and religion-unlike the First Amendment,

which imposes restrictions on civil government only. In short, a wall not only prevents the civil state from intruding on

the religious domain but also prohibits religion from influencing the conduct of civil government. The various First Amendment

guarantees, however, were entirely a check or restraint on civil government, specifically on Congress. The free press guarantee,

for example, was not written to protect the civil state from the press, but to protect a free and independent press from control

by the national government. Similarly, the religion provisions were added to the Constitution to protect religion and religious

institutions from corrupting interference by the national government, not to protect the civil state from the influence of,

or overreaching by, religion. As a bilateral barrier, however, the wall unavoidably restricts religion’s ability to

influence public life, thereby exceeding the limitations imposed by the First Amendment.

Herein lies the danger of this metaphor. The "high and impregnable" wall constructed by the modern Court has

been used to inhibit religion’s ability to inform the public ethic, to deprive religious citizens of the civil liberty

to participate in politics armed with ideas informed by their faith, and to infringe the right of religious communities and

institutions to extend their prophetic ministries into the public square. Today, the "wall of separation" is the sacred icon

of a strict separationist dogma intolerant of religious influences in the public arena. It has been used to silence religious

voices in the public marketplace of ideas and to segregate faith communities behind a restrictive barrier.

Federal and state courts have used the "wall of separation" concept to justify censoring private religious expression

(such as Christmas creches) in public, to deny public benefits (such as education vouchers) for religious entities, and to

exclude religious citizens and organizations (such as faith-based social welfare agencies) from full participation in civic

life on the same terms as their secular counterparts. The systematic and coercive removal of religion from public life not

only is at war with our cultural traditions insofar as it evinces a callous indifference toward religion but also offends

basic notions of freedom of religious exercise, expression, and association in a pluralistic society.

There was a consensus among the founders that religion was indispensable to a system of republican self-government.

The challenge the founders confronted was how to nurture personal responsibility and social order in a system of self-government.

Tyrants and dictators can use the whip and rod to force people to behave as they desire, but clearly this is incompatible

with a self-governing people. In response to this challenge the founders looked to religion (and morality informed by religious

faith) to provide the internal moral compass that would prompt citizens to behave in a disciplined manner and thereby promote

social order and political stability. The literature of the founding era is replete with this argument, no example more famous

than George Washington’s statement in his Farewell Address of September 19, 1796:

Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, Religion and morality are indispensable

supports. In vain would that man claim the tribute of Patriotism, who should labour to subvert these great Pillars of human

happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men and citizens . . . . And let us with caution indulge the supposition,

that morality can be maintained without religion . . . . [R]eason and experience both forbid us to expect that National morality

can prevail in exclusion of religious principle.

Believing that religion and morality were indispensable to social order and political prosperity, the founders

championed religious liberty in order to foster a vibrant religious culture in which a beneficent religious ethos would inform

the public ethic and to promote an environment in which religious and moral leaders could speak out boldly, without restraint

or inhibition, against corruption and immorality in civic life. Religious liberty was not merely a benevolent grant of the

civil state; rather, it reflected an awareness among the founders that the very survival of the civil state and a civil society

was dependent on a vibrant religious culture, and religious liberty nurtured such a religious culture. In other words, the

civil state’s respect for religious liberty is an act of self-preservation. The unfortunate consequence of 20th-century

jurisprudence is that the First Amendment, designed to protect and promote a vital role for religion in public life, has been

replaced with a wall of separation that, in the hands of the modern judiciary, has restricted religion’s place in the

polity.

Legacy

of Intolerance

In his recent book, Separation of Church and State, Philip Hamburger amply documents that the rhetoric

of separation of church and state became fashionable in the 1830s and 1840s and, again, in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Why? It accompanied two substantial waves of Catholic immigrants with their peculiar liturgy and resistance to assimilation

into the Protestant establishment: an initial wave of Irish in the first half of the century, and then more Irish along with

other European immigrants later in the century. The rhetoric of separation was used by nativist elements, such as the Know-Nothings

and later the Ku Klux Klan, to marginalize Catholics and to deny them, often through violence, entrance into the mainstream

of public life. By the end of the century, an allegiance to the so-called "American principle" of separation of church and

state had been woven into the membership oaths of the Ku Klux Klan. Today we typically think of the Klan strictly in terms

of their views on race, and we forget that their hatred of Catholics was equally odious.

Again, in the mid-20th century, the rhetoric of separation was revived and ultimately constitutionalized by

anti-Catholic elites, such as Justice Hugo L. Black, and fellow travelers in the ACLU and Protestants and Other Americans

United for the Separation of Church and State, who feared the influence and wealth of the Catholic Church and perceived parochial

education as a threat to public schools and democratic values. The chief architect of the modern "wall" was Justice Black,

whose affinity for church-state separation and the metaphor was rooted in virulent anti-Catholicism. Hamburger has argued

that Justice Black, a former Alabama Ku Klux Klansman, was the product of a remarkable "confluence of Protestant, nativist,

and progressive anti-Catholic forces . . . . Black’s association with the Klan has been much discussed in connection

with his liberal views on race, but, in fact, his membership suggests more about [his] ideals of Americanism," especially

his support for separation of church and state. "Black had long before sworn, under the light of flaming crosses, to preserve

‘the sacred constitutional rights’ of ‘free public schools’ and ‘separation of church and state.’"

Although he later distanced himself from the Klan on matters of race, "Black’s distaste for Catholicism did not diminish."

Black’s admixture of progressive, Klan, and strict separationist views is best understood in terms of anti-Catholicism

and, more broadly, a deep hostility to assertions of ecclesiastical authority. Separation of church and state, Black believed,

was an American ideal of freedom from oppressive ecclesiastical authority, especially that of the Roman Catholic Church. A

regime of separation enabled Americans to assert their individual autonomy and practice democracy, which Black believed was

Protestantism in its secular form.

To be clear, diverse strains of political, religious, and intellectual thought have embraced notions of separation

(I myself come from a faith tradition that believes church and state should operate in separate institutional spheres), but

a particularly dominant strain in 19th-century America was this nativist, bigoted strain. We must confront the uncomfortable

fact that the phrases "separation of church and state" and "wall of separation," although not necessarily expressions of intolerance,

have often, in the American experience, been closely identified with the ugly impulses of nativism and bigotry.

In conclusion, Jefferson’s figurative language has not produced the practical solutions to real world

controversies that its apparent clarity and directness led its proponents to expect. Indeed, this wall has done what walls

frequently do?it has obstructed the view, obfuscating our understanding of constitutional principles governing church-state

relationships. The rhetoric of "separation of church and state" and "a wall of separation" has been instrumental in transforming

judicial and popular constructions of the First Amendment from a provision protecting and encouraging religion in public life

to one restricting religion’s place and role in civic culture. This transformation has undermined the "indispensable

support" of religion in our system of republican self-government. This fact would have alarmed the framers of the Constitution,

and we ignore it today at the peril of our political order and prosperity.

Editor,

Douglas A. Jeffrey; Deputy Editor, Timothy W. Caspar; Assistant to the Editor, Patricia A. DuBois. The opinions expressed

in Imprimis are not necessarily the views of Hillsdale College. Copyright © 2006. Permission to reprint in whole or part is

hereby granted, provided the following credit line is used: “Reprinted by permission from IMPRIMIS, the national speech

digest of Hillsdale College, www.hillsdale.edu.” Subcription free upon request. ISSN 0277-8432. Imprimis trademark registered in U.S. Patent and

Trade Office #1563325.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

Wall Street Journal

www.wsj.com

COMMENTARY

The Top 1% . . . of What?

By ALAN REYNOLDS

December 14,

2006; Page A20

As many others have done, Virginia's Democratic

Senator-elect Jim Webb recently complained on this page of an "ever-widening divide" in America, claiming "the top 1% now takes in an astounding 16% of national income, up from 8%

in 1980." Those same figures have been repeatedly echoed in all major newspapers, including this one. Yet the statement is

clearly false. The top 1% of households never received anything remotely approaching 16% of personal income (national

income includes corporate profits). The top 1% of tax returns accounted for 10.6% of personal income in 2004. But that

number too is problematic.

The architects of these estimates, Thomas Piketty of École Normale Supérieure in Paris and Emmanuel Saez of the University of California at Berkeley, did not refer

to shares of total income but to shares of income reported on individual income tax returns -- a very different thing. They

estimate that the top 1% (1.3 million) of taxpayers accounted for 16.1% of reported income in 2004. But they explicitly exclude

Social Security and other transfer payments, which make up a large and growing share of total income: 14.7% of personal income

in 2004, up from 9.3% in 1980. Besides, not everyone files a tax return, not all income is taxable (e.g., municipal bonds),

and not every taxpayer tells the complete truth about his or her income.

For such reasons, personal income in 2004 was $3.3 trillion, or 34.4%, larger than the amount included in the

denominator of the Piketty-Saez ratio of top incomes to total incomes. Because that gap has widened from 30.5% in 1988, the

increasingly gigantic understatement of total income contributes to an illusory increase in the top 1%'s exaggerated share.

The same problems affect Piketty-Saez estimates of share of the top 5%, which contradict those from the Census

Bureau (which also exclude transfer payments). Messrs. Piketty and Saez figure the top 5%'s share rose to 31% in 2004 from

27% in 1993. Census Bureau estimates, by contrast, show the top 5%'s share of family income fluctuating insignificantly from

20% to 21% since 1993. The top 5%'s share has been virtually flat since 1988, aside from a meaningless one-time jump in 1993

when, as the Economic Policy Institute noted, "a change in survey methodology led to a sharp rise in measured inequality."

Unlike the Census Bureau, Messrs. Piketty and Saez measure income per tax unit rather than per family or household.

They maintain that income per tax unit is 28% smaller than income per household, on average. But because there are many more

two-earner couples sharing a joint tax return among high-income households, estimating income per tax return exaggerates inequality

per worker.

The lower line in the graph shows that the amount of income Messrs. Piketty and Saez attribute to the top 1%

accounted for 10.6% of personal income in 2004. That 10.6% figure looks much higher than it was in 1980. Yet most of that

increase was, as they explained, "concentrated in two years, 1987 and 1988, just after the Tax Reform Act of 1986." As Mr.

Saez added, "It seems clear that the sharp, and unprecedented, increase in incomes from 1986 to 1988 is related to the large

decrease in marginal tax rates that happened exactly during those years."

That 1986-88 surge of reported high income was no surprise to economists who study taxes. All leading studies

of "taxable income elasticity," including two by Mr. Saez, agree that the amount of income reported by high-income taxpayers

is extremely sensitive to the marginal tax rate. When the top tax rate goes way down, the amount reported on tax returns goes

way up. Those capable of earning high incomes had more incentive to do so when the top U.S. tax rate dropped to 28% in 1988 from 50% in 1986. They also had less incentive to maximize

tax deductions and perks, and more incentive to arrange to be paid in forms taxed as salary rather than as capital gains or

corporate profits.

The top line in the graph shows how much of the top 1%'s income came from business profits. In 1981, only 7.8%

of the income attributed to the top 1% came from business, because, as Mr. Saez explained, "the standard C-corporation form

was more advantageous for high-income individual owners because the top individual tax rate was much higher than the corporate

tax rate and taxes on capital gains were relatively low." More businesses began to file under the individual tax when individual

tax rates came down in 1983. This trend became a stampede in 1987-1988 when the business share of top percentile income suddenly

increased by 10 percentage points. The business share increased again in recent years, accounting for 28.4% of the top 1%'s

income in 2004.

As was well-documented years ago by economists Roger Gordon and Joel Slemrod, a great deal of the apparent increase

in reported high incomes has been due to "tax shifting." That is, lower individual tax rates induced thousands of businesses

to shift from filing under the corporate tax system to filing under the individual tax system, often as limited liability

companies or Subchapter S corporations.

IRS economist Kelly Luttrell explained that, "The long-term growth of S-corporation returns was encouraged by

four legislative acts: the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1990, the Revenue Reconciliation Act

of 1993, and the Small Business Protection Act of 1996. Filings of S-corporation returns have increased at an annual rate

of nearly 9.0% since the enactment of the Tax Reform Act of 1986."

Switching income from corporate tax returns to individual returns did not make the rich any richer. Yet it caused

a growing share of business owners' income to be newly recorded as "individual income" in the Piketty-Saez and Congressional

Budget Office studies that rely on a sample of individual income tax returns. Aside from business income, the top 1%'s share

of personal income from 2002 to 2004 was just 7.2% -- the same as it was in 1988.

In short, income shifting has exaggerated the growth of top incomes, while excluding a third of personal income

(including transfer payments) has exaggerated the top groups' income share.

There are other serious problems with comparing income reported on tax returns before and after the 1986 Tax

Reform. When the tax rate on top salaries came down after 1988, for example, corporate executives switched from accepting

stock or incentive stock options taxed as capital gains (which are excluded from the basic Piketty-Saez estimates) to nonqualified

stock options reported as W-2 salary income (which are included in the Piketty-Saez estimates). This largely explains why

the top 1%'s share rises with the stock boom of 1997-2000 then falls with the stock market in 2001-2003.

In recent years, an increasingly huge share of the investment income of middle-income savers is accruing inside

401(k), IRA and 529 college-savings plans and is therefore invisible in tax return data. In the 1970s, by contrast, such investment

income was usually taxable, so it appears in the Piketty-Saez estimates for those years. Comparing tax returns between the

1970s and recent years greatly understates the actual gain in middle incomes, and thereby contributes to the exaggeration

of top income shares.

In a forthcoming Cato Institute paper I survey a wide range of official and academic statistics, finding no

clear trend toward increased inequality after 1988 in the distribution of disposable income, consumption, wages or wealth.

The incessantly repeated claim that income inequality

has widened dramatically over the past 20 years is founded entirely on these seriously flawed and greatly misunderstood

estimates of the top 1%'s alleged share of something-or-other.

The

politically correct yet factually incorrect claim that the top 1% earns 16% of personal income appears to fill a psychological

rather than logical need. Some economists seem ready and willing to supply whatever is demanded. And there is an endless political

demand for those able to fabricate problems for which higher taxes are, of course, the preferred solution. In Washington higher taxes are always the solution; only the problems change.

Mr. Reynolds, a senior fellow with the Cato Institute, is the author of "Income and

Wealth" (Greenwood Press, 2006).

Phil Brennan, NewsMax.com

Analysis: Ten Good Reasons to

Vote GOP

Thursday, Oct. 26, 2006

If the polls are to be believed, the Republicans who control the White House and Congress

are in trouble.

Their problem?

People vote their pocketbooks, or wallets, the old adage goes.

But the economy is booming. Even gasoline prices have plummeted. Unemployment, the bogeyman

of politicians, has shrunken to a record low point.

As for the security matter, since 9/11, the worst attack on American soil since the

Civil War, the United

States has been free

of any significant terrorist attack. None. Zippo. Zilch.

If Americans do vote the GOP out of either House of Congress, many of these accomplishments

are threatened.

Should Democrats get control of the House of Representatives, they have already promised

that one of the Republican initiatives that made all these things possible will be rolled back.

Higher taxes -- and with it, economic recession and more unemployment.The Democrats will

also signal the terrorists a "victory" for their side with a push for a quick withdrawal from Iraq. Remember, the Congress,

not the president, funds our troops abroad. A Democratic Congress will most assuredly withhold funding unless Bush relents.

The list of Republican accomplishments is both long and real, and provides the platform

upon which even greater results will be built under a Republican Congress and White House.

For sure, the GOP has had its share of shortcomings. The economy could be doing better.

The deficit could be smaller. The postwar plans in Iraq

could have been better implemented.

If anything, the Republicans are facing a message deficit. The liberal media establishment

is just not letting them tell their story to the American people.

Here are 10 good reasons why you should vote Republican come election day. You won't hear

about them on ABCCBSNBC News.

Reason #1. The economy is kicking butt. It is robust, vibrant, strong and growing. In the

36 months since the Bush tax cuts ended the recession that began under President Clinton, the economy has experienced astonishing

growth. Over the first half of this year, our economy grew at a strong 4.1 percent annual rate, faster than any other major

industrialized nation. This strong economic activity has generated historic revenue growth that has shrunk the deficit. A

continued commitment to spending restraint has also contributed to deficit reduction.

Reason #2. Unemployment is almost nil for a major economy, and is verging on full employment.

Recently, jobless claims fell to the lowest level in 10 weeks. Employment increased in 48 states over the past 12 months ending

in August. Our economy has now added jobs for 37 straight months.

Reason #3. The Dow is hitting record highs. In the past few days, the Dow climbed above

12,000 for the first time in the history of the stock market, thus increasing the value of countless pension and 401(k) that

funds many Americans rely on for their retirement years.

Reason #4. Wages have risen dramatically. According to the Washington Post, demand for

labor helped drive workers' average hourly wages, not including those of most managers, up to $16.84 last month -- a 4 percent

increase from September 2005, the fastest wage growth in more than five years. Nominal wage growth has been 4.1 percent so

far this year. This is better or comparable to its 1990s peaks. Over the first half of 2006, employee compensation per hour

grew at a 6.3 percent annual rate adjusted for inflation. Real after-tax income has risen a whopping 15 percent since January

2001. Real after-tax income per person has risen by 9 percent since January 2001.

Reason #5. Gas prices have plunged. According to the Associated Press, the price of

gasoline has fallen to its lowest level in more than 10 months. The federal Energy Information Administration said Monday

that U.S. motorists paid $2.21 a gallon on average for regular grade last week,

a decrease of 1.8 cents from the previous week. Pump prices are now 40 cents lower than a year ago and have plummeted by more

than 80 cents a gallon since the start of August. The previous 2006 low for gasoline was set in the first week of January,

when pump prices averaged $2.238. In the week ending Dec. 5, 2005, prices averaged $2.19. Today, gasoline can be found for less than $2 a gallon in many parts of the country.

Reason #6. Since 9/11, no terrorist attacks have occurred on U.S. soil. Since 9/11 the U.S. has not been attacked by terrorists thanks to such programs

as the administration's monitoring of communications between al-Qaida operatives overseas and their agents in the U.S. and

the monitoring of the international movement of terrorist funds -- both measure bitterly opposed by Democrats.

Reason #7. Productivity is surging and has grown by a strong 2.5 percent over the past

four quarters, well ahead of the average productivity growth in the last 30 years. Strong productivity growth helps lead to

the growth of the Gross Domestic Product, higher real wages, and stronger corporate profits.

Reason #8. The Prescription Drug Program is working. Despite dire predictions that most

seniors would refrain from signing up to the new Medicare prescription benefits program, fully 75 percent of all those on

Medicare have enrolled, and the overwhelming majority say they are happy with the program.

Reason #9. Bush has kept his promise of naming conservative judges. He has named two conservative

justices to the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John G. Roberts and Justice Samuel Alito. In addition, he has named conservative

justices who are devoted to the Constitution as it is written and not as activist liberal judges think it means. The strong

likelihood that one or more justices will retire from the Supreme Court makes it mandatory for the Republicans to hold the

Senate and have a chance to name new conservative justices.

Reason #10. The deficit has been cut in half three years ahead of the president's 2009

goal, with the 2006 fiscal year budget deficit down to $248 billion. The tax cuts have stimulated the economy and are working.

In contrast to this stunning record of real achievement, the Democrats offer no real

plans for the way they want to improve America

or make us safer.

Instead, issues like the Mark Foley scandal have been used to smokescreen their own lack

of ideas in a public debate.

The choice voters will make is whether they want higher taxes and less security by surrendering

the tools used to combat terrorism or lower taxes and the continued use of tools like the Patriot Act, terrorist surveillance,

terrorist interrogations and missile defense.

Consider what leading Democrats are promising if they gain control of Congress.

· Rep. Charlie Rangel, D-N.Y., who would lead the House tax-writing committee if

Democrats win in November, said he "cannot think of one" tax cut he would renew. That agenda would result in $2.4 trillion

tax increase over the next 10 years.

· If Democrats take majorities in the House and Senate, the average family of four

can expect to pay an average of $2,000 more in taxes.

· The leader of House Democrats and the woman who would be speaker of the House,

Rep. Nancy Pelosi, D-Calif., said after 9/11 that she "doesn't really consider ourselves at war ... we're in a struggle against

terrorism."

· By opposing the Patriot Act, terrorist surveillance missile defense and even interrogating

the most dangerous terrorists captured on the battlefield, Democrats are in direct opposition to the vital tools we use to

fight terrorism.

· Many Democrats, including the prospective House Ways and Means chairman, favor cutting off funding for the war in Iraq .

· Democratic leaders have made it clear that they see investigations and impeachment

as viable options should they take control of Congress. They are therefore promising to tie the hands of the president and

his administration in the middle of a war.

· Democrats want to reverse the president's economic policies that have led to a

historically strong economy.

Enough said.

The Virginian-Pilot

Where

Local Legislators

Stand

On Transportation Issues

By Tom Holden and Christina Nuchols

© September 11, 2006

Here,

in brief, are the views of local legislators who were asked questions recently about how best to deal with the region's transportation

problems.

Del. Kenny Alexander, D-Norfolk: wants a

penny-on-the-dollar sales tax or a one-half-percent increase in the income tax to help pay for transportation needs. Does

not favor using general fund money for long-term investments. Supports building the third crossing and the creation of a regional

transportation authority to collect tolls.

Del. Bill Barlow, D- Isle of Wight: declined

to answer.

Del. John Cosgrove, R-Chesapeake: declined

to answer.

Del. Sal Iaquinto, R-Virginia Beach: backs a plan creating a new Hampton Roads transportation authority with the power to impose tolls on new and existing

roads. Would consider an increase of local licensing fees, car rental car fees and hotel fees, and diverting some money from

the general fund to finance road projects.

Del.

Algie Howell Jr., D-Norfolk: declined to answer.

Del. Johnny Joannou, D-Portsmouth: wants

additional tunnel capacity to relieve congestion at the Midtown, Downtown and Hampton Roads tunnels. Favors expanding U.S.

460 and creating a regional transportation authority - if its members are directly elected.

Del. Chris Jones, R-Suffolk: backs a plan

creating a new Hampton Roads transportation authority with the power to impose tolls on new and existing roads. Would consider

increasing local licensing fees, car rental car fees and hotel fees and diverting some money from the general fund.

Del. Lynwood W. Lewis Jr., D-Accomac: declined

to answer.

Del. Ken Melvin, D-Portsmouth: declined to

answer.

Del.

Paula Miller, D-Norfolk: favors raising new income for transportation. Opposes relying on the general fund for long-term

transportation needs. Favors tolls and higher fees on bad drivers to help pay for new roads. Supports building the third crossing

and creating a regional authority to raise money - if there is no statewide plan.

Del. Bob Purkey, R-Virginia Beach: declined to discuss transportation issues, saying it would damage

efforts to build support for new proposals.

Del. Lionell Spruill Sr., D-Chesapeake: supports

raising more money for transportation but says it's a statewide responsibility. Opposes creating a regional transportation

authority, using the general fund for long-term needs or putting tolls on existing roads. Favors increasing gas taxes.

Sen. Kenneth Stolle, R-Virginia Beach: supports

using some general fund revenue for transportation as long as education and public safety are protected. Opposes diverting

existing sales or income taxes. Favors using more insurance premiums for road-building. Has supported plans calling for tolls

or local sales taxes to pay for priority projects.

Sen. Frank Wagner, R-Virginia Beach: has backed efforts relying on tolls or local taxes to pay for road

and rail projects. Says a regional plan alone will not be adequate unless new revenues are generated for statewide maintenance.

Del. Bob Tata, R-Virginia Beach: supports tolls on new roads, bridges and tunnels, and tolls on HOV

lanes allowing single-occupant vehicles during restricted hours. Supports diverting a portion of revenues now going to general

government operations such as schools and health care and using the money for transportation.

Del. Leo Wardrup Jr., R-Virginia Beach: supports

using tolls for new and existing roads, bridges and tunnels, and tolls on HOV lanes for single-occupant vehicles. Open to

taking revenues now earmarked for general operating expenses and using the money for road and rail improvements. He opposes

any regional authority that has the power to tax.

Sen. Harry Blevins, R-Chesapeake: declined

to discuss transportation issues for fear of hurting efforts to build support for new proposals. Has voted in favor of setting

up a regional authority in Hampton Roads with the power to collect tolls. Has voted for a bill that would allowed localities

to impose a sales tax for transportation. Has supported a statewide transportation plan that taxed fuel and motor vehicle

sales.

Sen. Louise Lucas, D-Portsmouth: supports

plans to boost investment in transportation projects through increases in taxes, tolls and fees. Opposes diverting existing

revenues away from education and health care to spend on transportation.

Sen. Yvonne Miller, D-Norfolk: supports plans

to boost investment in transportation projects through increases in taxes, tolls and fees. Opposes diverting existing revenues

away from education and health care to spend on transportation. Wants more state money invested in mass transit.

Sen. Frederick Quayle, R-Suffolk: supports

plans to boost investment in transportation projects through increases in taxes, tolls and fees. Sponsored legislation that

would set up a regional authority with the power to collect tolls on roads, bridges and tunnels in Hampton Roads. The measure

also would allow local governments to increase the sales tax to pay for transportation projects.

Sen. Nick Rerras, R-Norfolk: supports plans

to pay for transportation improvements using budget surplus and taxes. Would consider increases in the sales tax and auto

titling fee, and bad driver penalties and tolls. Prefers not to increase the gas tax.

Wall Street Journal

REVIEW

& OUTLOOK

Tax Tidal

WAVE

October 6, 2006; Page A14

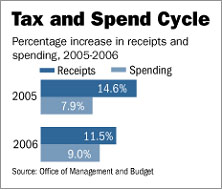

Congress keeps breaking the Beltway Book of World Records for spending money, but the government will soon report

that the federal budget deficit for the just-completed 2006 fiscal year fell to about $260 billion.

What's the secret of this deficit success that you aren't reading much about this election year? It isn't spending

restraint. The federal budget expanded to $2.7 trillion last year, a 9% increase, or three times the inflation rate. Over

the past six years the federal budget has increased by 49.2%.

The main cause of the deficit decline -- 90% of it, says White House budget director Rob Portman -- is

a tidal wave of tax revenue. Tax collections have increased by $521 billion in the last two fiscal years, the largest two-year

revenue increase -- even after adjusting for inflation -- in American history. If you're surprised to hear that, it's probably

because inside Washington this is treated as the only secret no one wants to print. On the

few occasions when the media pay attention to the rise in tax collections, they scratch their heads and wonder where this

"surprising" and "unexpected windfall" came from.

One place it has come from are corporations, whose tax collections have climbed by 76% over the past two years

thanks to greater profitability. Personal income tax payments are up by 30.3% since 2004 too, despite the fact that the highest

tax rate is down to 35% from 39.6%. The IRS tax-return data just released last month indicates that a near-record 37% of those

income tax payments are received from the top 1% of earners -- "the rich," who are derided regularly in Washington for not

paying their "fair share."

More good news is that dividend-tax payments appear to be up as well, even though the tax rate was lowered to

15% from as high as 39.6%. A National Bureau of Economic Research study found that "after a continuous decline in dividend

payments over more than two decades, total regular dividends have grown by nearly 20%" and that this reversal happened at

"precisely the point at which the lower tax rate was proposed and subsequently applied retroactively." There hasn't been a

purer validation of the Laffer Curve since Ronald Reagan rode off into the sunset.

As for the budget deficit, at $260 billion it is now about 2% of our $13 trillion economy, well below the

2.7% average of the last 40 years. Most states and localities are also afloat in tax collections, and including their revenue

surpluses brings the total U.S. public sector borrowing down to roughly 1.5% of GDP. Not too shabby

given that we're waging a war on terrorism and Congress spent $50 billion last year on Hurricane Katrina clean-up.

Anyway, we thought our taxpaying readers might like to know how much you've all been contributing to the

falling deficit -- the best-kept secret in Washington.

Back to Basics for the Republican Party

A book by Michael Zak

Text Below from the website http://www.republicanbasics.com/1270328.html

For the past century and a half, the Republican Party has proven to be the most effective political organization ever to champion

equality and human rights in the United States and around the world.

From President Lincoln's victory in the Civil War to President Reagan's victory in the Cold War, the GOP shares credit for

the ability of hundreds of millions of people to live in freedom.

Many communities claim credit as the birthplace of the Grand Old Party. Perhaps the most significant place was

in Ripon, Wisconsin on March 20, 1854.

The agenda was simple at this schoolhouse gathering: oppose the pro-slavery policies of the Democratic Party.

Democrat House and Senate majorities and a Democrat President incited the 1854 meeting by approving a bill by Senator Stephen

Douglas (D-IL) to allow slavery into the western territories. Opponents of slavery expressed their outrage at

town meetings and rallies. The issue, as Lincoln foresaw, was whether the United

States would become all slave or all free. The Ripon

meeting earned particular attention from the national press, and anti-slavery Americans soon adopted the name "Republican"

nationally.

Republicans held our first state convention in Jackson, Michigan on July 6, 1854. That fall, the GOP swept to victory throughout the North. Other anti-slavery Members

of Congress joined the party, so that less than two years later, on February 2, 1856, Republicans elected a Republican Speaker of the House.

The Republican National Committee first met the next month, to coordinate opposition to the pro-slavery policies of

the Democrats, also known then as "slaveocrats." And that summer, Republicans held our first national convention.

There, we nominated our first presidential candidate, the Georgia-born former California Senator John Fremont. Four

years later, we won the White House for the "Great Emancipator."

As the nation sacrificed during the Civil War, Republicans planned the most significant amendments ever to our Constitution

and enacted — despite fierce opposition from the Democrats — the 13th Amendment to ban slavery, the 14th Amendment

to protect all Americans regardless of the color of their skin, and the 15th Amendment to extend voting rights to African-Americans.

The Republicans' 1875 Civil Rights Act guaranteed equal access to public accommodations without regard to race.

Struck down by the Supreme Court in 1883, this law would be reborn as the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

"Every man that wanted the privilege of whipping another man to make him work for nothing, and pay him with lashes on his

naked back, was a Democrat. Every man that raised bloodhounds to pursue human beings was a Democrat. Every man

that cursed Abraham Lincoln because he issued the Emancipation Proclamation was a Democrat." Robert Ingersoll, 1876

For its first 80 years, the Republican Party was the only one to provide a home for African-Americans. Until well into

the 20th century, every African-American Member of Congress was a Republican. The same was true for nearly all state

legislators and other elected officials. In 1888, Republican Senator Aaron Sargent introduced the "Susan B. Anthony"

Amendment to the Constitution, according women of all races the right to vote. Strong Democrat opposition to what

would become the 19th Amendment delayed

ratification until 1920.

The year 2004 was the 150th anniversary of the GOP as well as the 50th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, a watershed of the modern-day

civil rights movement. In May 1954, former Republican Governor and GOP vice presidential candidate Earl Warren,

appointed Chief Justice by Republican President Eisenhower, wrote this landmark decision declaring that "separate but equal"

is inherently unconstitutional. To help enforce this principle, the Eisenhower administration drafted the 1957

Civil Rights Act and guided it to passage over a Democrat filibuster.

The Republican Leader in the Senate, Everett Dirksen (R-IL), wrote the 1960 Civil Rights Act. Senator Dirksen

was the person most responsible for defeating the Democrat filibuster against the 1964 Civil Rights Act. The 1964

Civil Rights Act passed the House of Representatives with 80% Republican support but only 61% of Democrats. In

the Senate, 82% of Republicans supported the bill compared to 69% of Democrats. Similarly, the 1965 Voting Rights

Act was supported in Congress by a higher percentage of Republicans than Democrats. Democrats vigorously opposed

Republican efforts to protect the civil rights of African-Americans, from Reconstruction until well into the 20th century.

In much of the country, racist Democrats virtually destroyed the Republican Party, which did not become a force in those areas

until President Reagan's message of freedom and equality prevailed in the 1980s. Today, the Republican Party continues

its historical commitment to civil rights at home and around the world.

|

|

|

|

|